Historical background

The name of the bag is derived from Haithabu (German) or Hedeby (English) after the location of an archaeological excavation in present-day Germany. The excavation yielded a number of narrow carved wooden pieces, rounded and with holes on both ends and a set of narrow elongated slots along the straight length (Figure 1). Some of the pieces had textile remnants through the slots, although nothing survived to the present day. The current interpretation is that they are bag handles after comparison with an earlier Sami find (Figure 2). They have a surprisingly simple but effective design; the wooden handles hold and maintain the shape of the bag and a single shoulder cord through the holes allows you to carry it, while keeping the bag closed at the same time.

Figure 1: Photograph of the wooden bag handles on display in the Haithabu Museum (http://europa.org.au/index.php/articles/21-bags).

Figure 2: Photograph of a Sami leather bag with antler handles .

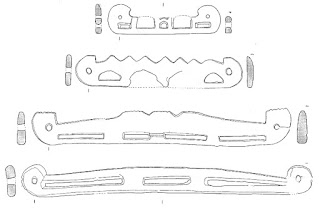

A total of fourteen pieces where found at the Haithabu excavation site. Five are made from ash, five others from maple and the remaining four are not specified. They have rounded ends with holes drilled through for the carrying cord. The bottom edges are mostly straight, the top edges are wavy or with notches. Elongated slots along the bottom serve to attach the bag. Dimensions vary from 181 to 496 mm in length (Figure 3), a thickness of 7 to 13 mm, and 29-52 mm wide in the center part. The semicircular ends have diameters ranging from 31 to 61 mm, and have a 7 to 10 mm diameter (drilled) hole in the center. Two of the pieces were identical (HbH.119.001-002), i.e. a pair, and it is therefore assumed that the others should all have been part of pairs.

Figure 3: Four of the wooden pieces, ranging in length from 181 to 496 mm: HbH.119.003, HbH.119.012, HbH.119.013, and HbH.119.014 (top to bottom).

Creating the bag handles

I decided to create an accurate reproduction of the HbH.199.003 wooden handles. This choice was partially a matter of taste, but mostly a matter of size. The original size of this handle is 181 mm, which is almost a perfect match to the width of the fabric that I planned to use for the bag. I started by copying and scanning the top handle in Figure 3. The design was then enlarged and printed to get a length of 205 mm, slightly larger than the original, but a better match with the fabric. From the ratio of the length and thickness in Figure 3, I computed a corresponding thickness of about 9 mm. Since the original piece was damaged along the top, curved arches were added in a way that looks consistent with and in good proportion to the curved end pieces and the overall design.

Florian Westphal does not list the wood type for this particular handle, so I decided to use ash given that five of the fourteen handles were made from ash and the fact that a suitable ash log was available to me (a leftover piece of the ash logs that I harvested for another project). The log was split along the centerline with an ax into five boards. The center board was discarded in favor of the two boards on either side. This ensures that the wood grain is predominantly parallel with the face of the handle, avoiding potentially weak spots at the slot locations. The two boards were then shaped to the correct thickness and to a slightly larger outer dimension using an ax, a draw blade and a coarse rasp and finished with a file to a smooth outer surface.

The outline of the handle and the locations of the holes for the shoulder strap and the other five holes were traced onto each board using the real size printed design. The holes were cut out using a drill and chisels and finished with several files. When everything else was completely finished, the outline was cut out with a saw. The final handles were finished with linseed oil to help preserve and protect the wood.

The tools required to make the handle (axe, hammer, several chisels and files, rasp, draw blade, saw, and spoon drills) were quite common in Viking Age Haithabu. Examples of all these tools were found in the Mästermyr chest, a Viking Age tool chest from Gotland. Functionally identical modern versions of these hand tools were used to create the handles with the exception of the spoon drills and the saw. I have not yet laid my hands on spoon drills, so a modern drill was used instead. Due to an elbow injury, use of a handsaw was not an option, so a band saw was used to cut the outline of the handles.

Figure 4: Reconstruction of the HbH.119.003 handle.

Weaving the fabric for the bag

There is no actual archaeological evidence for the bags that went with the Haithabu handles, but we can make an educated guess as to the shape, size and material. The width is dictated by the length of the handles, while pictorial evidence of period shoulder bags suggests an almost square form. The Sami bag in Figure 2 was made from leather, but textile evidence with some of the Haithabu handles at the time of excavation makes it plausible that fabric was used as well. I settled on the latter, since my motivation for this project stemmed from the desire to make something nice and useful with my first piece of hand woven cloth.

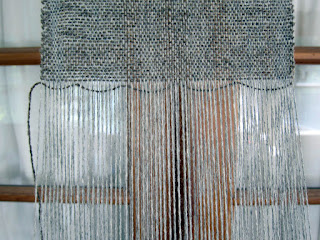

The cloth for the bag was woven on a reproduction Viking Age warp-weighted loom. A tablet woven band was used as the starting band for the warp. The same (store bought) wool was used for the warp and the weft. The loom was setup for plain tabby weave with a warp count of about 6/cm, and a weft count about 4/cm. A single piece, the full width of the woven fabric, was used for the front, the bottom and the back of the bag. Two additional pieces, half the width of woven fabric were used for each side, they are added to allow the bag to open wide enough for practical use. Selvage on both sides was obtained by weaving both sides at the same time after splitting the warp in two equal sections (Figure 5).

Figure 5: The finished fabric before cutting it in three pieces.

Assembling the bag

The three pieces of fabric for the bag were hand sewn together. Running stitch was used to join each seam; both edges were then folded down and secured with a whip stitch. The top of the bag was hemmed by folding the edges back once and whip stitch along the raw edge. A linen liner was added to protect the wool fabric and make the inside of the bag stronger for practical use. The liner was assembled in a similar fashion with the exemption of the reversed seams and hems. The outer wool fabric and the liner were joined with a running stitch along the hems.

After the bag was completed, the wooden handles were attached with a thick yarn stitched through the hems and looped through the elongated slots. Finally, a shoulder band was braided from three strings of leather and tied to the bag handles through the holes in each of the round ends.

Learning points

Handles:

Using period hand tools for wood working is fun and surprisingly efficient. I hope to get spoon drills in the near future, so that I can experiment with those as well.

Weaving:

While weaving the header band, I passed only a single weft tread for each turn of the cards (this becomes the warp on the loom), resulting in a fairly open warp, making it hard to maintain a constant width during the weaving. In a current weaving project, I passed two weft threads for each quarter turn of the cards, reducing this issue significantly. To prevent “sagging” of the warp, it must be tied to the cloth beam at more positions.

Shoulder strap:

The braided leather band is a bit to thick and stiff for easy opening and closing of the bag. I plan to either weave or braid a cloth shoulder band to replace the current leather strap.

Find a downloadable version of this post with its companion photo journal at:

https://www.academia.edu/33710073/Viking_hand_bag_based_on_the_Haithabu_find

Bibliography

Arwidsson, Greta and Berg, Gosta (1999), “The Mästermyr Find: A Viking Age Tool Chest from Gotland”, Larson Publishing Company (Lompoc, CA)

Johnson, Jennifer (2015) “Viking Stitchery”, SCA class handout by Hefðharkona Reyni-Hrefna.

Schietzel, Kurt (2014) “Spurensuche Haithabu: Archäologische Spurensuche in der frühmittelalterlichen Ansiedlung Haithabu. Dokumentation und Chronik 1963-2013”,

Wachholtz Verlag, Murmann Publishers (Neumünster/Hamburg).

Westphal, Florian (2006) “Die Holzfunde von Haithabu”, Wachholtz Verlag (Neumünster).